Austin and the Limits of YIMBY

The supposed success story of Austin illustrates the failure of market urbanist policies to achieve real affordability

The market urbanists have seized on an example closer to home than Tokyo to illustrate the supposed success of abundant housing policy: Austin, Texas.

The case made for Austin is that it responded to a tech-fueled economic and population boom over the early pandemic years with a relaxed zoning policy, allowing the market to respond with supply matching demand. This resulted in declining rents as an influx of new units brought tighter competition to the rental market.

Much like Tokyo, this all seems compelling enough at first glance. A closer analysis brings several issues to light with the narrative. Namely, the rent decline is a misleading snapshot of the broader market cycle, affordability remains challenging for most renters, and housing growth has come in tandem with sprawl and displacement. Ultimately, the case of Austin highlights the inadequacy of a market-driven approach to providing housing, which we must do better than.

Have Rents Really Gone Down?

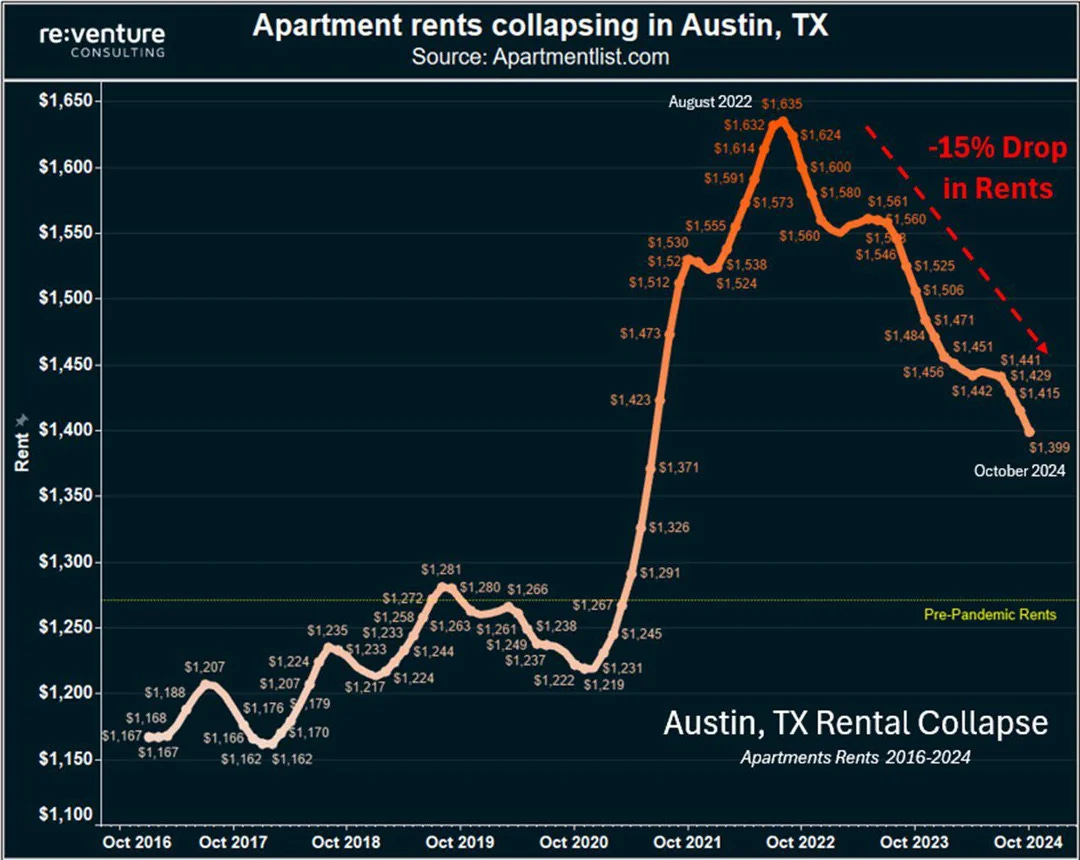

The most highly touted stat is that Austin rents declined 15% from their peak. You may have seen this chart illustrating a “rental collapse” in the city 2022 to 2024.

This is true at face value, but glosses over the broader trend. It is also true that rents in Austin are much higher than they were 5 years ago.

The above is my somewhat tongue-in-cheek DIY chart, but it illustrates an important fact - Austin experienced one of the largest rent inflations in the country during the early part of the pandemic. Between January 2021 and January 2022, Austin saw rent increases of over 35%, the second highest in the nation following Portland. From 2022 to 2023, the rate of rent increases slowed, reaching “only” 10% year over year, before turning negative in 2024.

Over the past few decades, the broader trend of the Austin market has, of course, been rising rents punctuated by small dips.

The recent celebrated rent decline occurred in the context of the rent previously rising to an unprecedented, exceptional peak. It is more accurate to see the falling rents in 2024-25 as a recalibration from a temporary bubble, rather than a sustainable trend towards greater affordability. It’s also worth noting that the rent decline partially coincides with a number of tech companies, and their workers, leaving Austin.

Boom and Bust

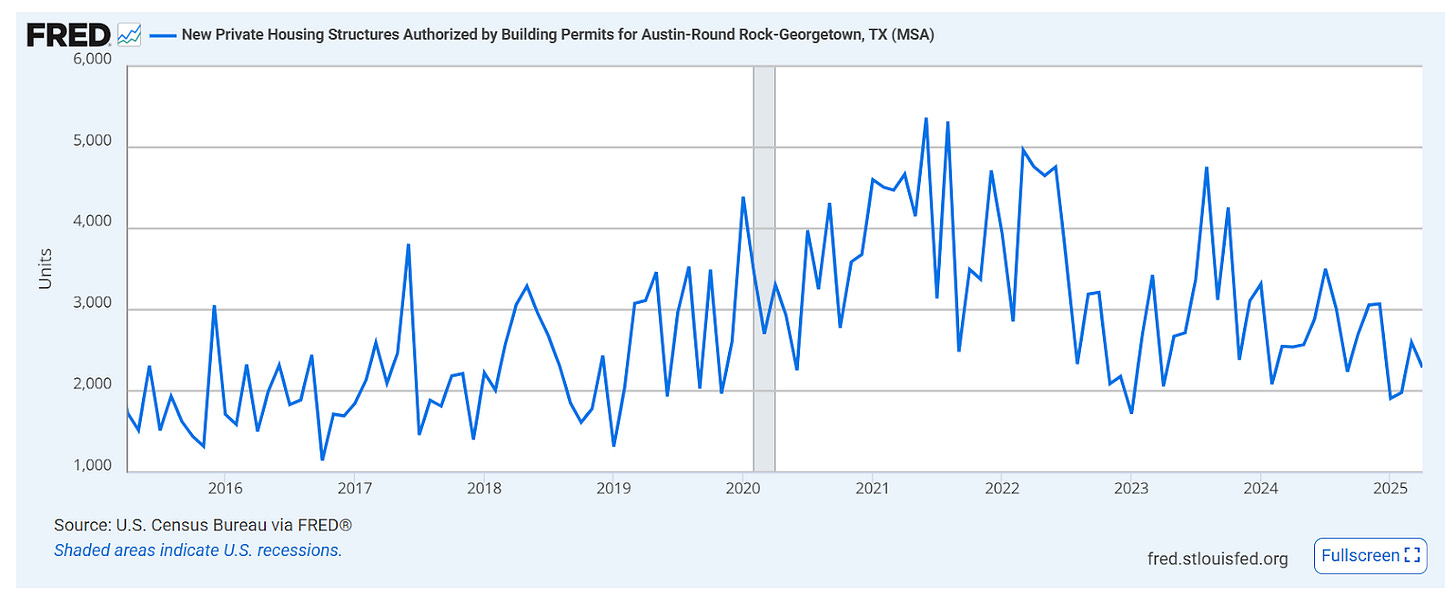

Austin housing developers are beginning to respond to the price dip by pulling back on construction. This is a straightforward economic mechanism – lower prices mean less profit to be made by building. YIMBYs readily acknowledge this when criticizing policies like inclusionary zoning and rent control.

Residential building permits for the Austin metro area are already down significantly from their peak, and continue to fall.

Experts predict that Austin rent prices will begin to rise again by the first quarter of 2026 as many investors pull back from the market. When we say that the rent declined, it's more accurate to view it as part of a standard housing market cycle where prices re-adjust to a new equilibrium, but don’t bring widespread affordability. On a longer time scale, rent trends ever upward. A temporary downturn does not imply that there will be a sustainable, ongoing trend to increase production and drive prices ever-lower.

If this is the best case scenario for market urbanism in the US, it is not very inspiring. As of 2023, over half of Austin renters are spending more than 30% of their income on housing - an increase from 2022. And Austin continues to rank as the most expensive Texas city to rent in.

Moreover, the change in rent burden has most strongly impacted working class renters making between $30,000 and $75,000. This suggests that the high-end building boom is not resulting in affordability for those with lower wages, and may even be exacerbating their struggle.

Given the severity of the affordable housing crisis, both in Austin and nationally, much more is needed outside of market-based reforms to actually address the problem. We should not be satisfied with a society where over 50% of renters are struggling to make ends meet due to the cost of housing.

Loss of Affordable Housing

An overlooked downside of booming construction is the potential loss of existing affordable housing. This can occur both directly, through demolition for redevelopment, and indirectly, through development inducing local rent increases in lower-rent housing. Recently, an apartment complex in northwest Austin with “naturally occurring” affordable units was approved for rezoning to be demolished and replaced with high-end housing. The tenants will likely be forced to move to less affordable, less conveniently located units, if indeed they can find housing at all.

This is the predictable outcome of a “let them build” approach that does not adequately protect existing tenants. Planning policy should seek to either preserve these existing affordable units, or ensure 1:1 replacement with new affordable housing and guaranteed units for displaced residents.

The Role of Sprawl

Austin’s geography is a major underlying reason for its relative affordability, particularly in comparison to large coastal cities such as New York and San Francisco. Austin has few major geographic constraints, such as oceans or mountains, that limit its outward expansion. It can therefore respond more flexibly to a demand shock than a city like San Francisco, regardless of differences in regulatory constraints.

There is more land available in the suburban fringe, which can be developed more cheaply due to lower land costs. Around half of recent new construction in the Austin metro area is single family homes, indicating that greenfield development is supporting supply increases, not just high density infill.

This can also be seen in the city’s expanding urban footprint. According to research by the Center for Geospatial Analysis at William & Mary, “...there was clearly a significant increase in urban area from 1990 to 2020 according to the Supervised Classification LULC images and subsequent calculations. Urban area increased from 6% to 15% in a matter of 30 years over approximately 25,965 square kilometers. This means that in a 30 year period, the Austin, Texas region went from containing approximately 1558 square kilometers of developed land to containing approximately 3,895 square kilometers of developed land which is an increase of 2,337 km^2, or a 150% increase.”

Even within the inner urban core, land prices are not comparable. Using a comprehensive database of land prices by zip code, I found that the land price for one of Austin’s central downtown zip codes (78703) was around $5.8 million per acre, while a San Francisco zip code in the sleepy Sunset neighborhood (94122) came to approximately $22 million.

Ignoring this fundamental difference paints a misleading picture. The most important factor is the relative availability of cheap land on which to build. While Austin has undergone substantial economic and population growth over the past decades, it is still nowhere near the economic maturity of San Francisco or New York City. Rural Kansas is also cheap to live in and to build, but we don’t take this as an indication that its zoning policies are responsible for this fact.

A recent study analyzed the patterns of housing development in major cities in both California and Texas, and found a common underlying trend - as cities mature, they move from building sprawl to a greater share of more costly infill. “As these MSAs grow, we see that fewer new net units are built at the periphery and a smaller share of the new units are built as single-family detached houses. As a greater share of new net units are built in infill locations, more units are built using higher-density—and more costly—multifamily housing construction techniques. Interestingly, we see these housing supply patterns in both “pro-growth” MSAs and “highly regulated” MSAs.”

Ultimately, sprawl imposes large costs both environmentally and economically, and can only go so far before commuting limits are reached and infill becomes the only option for continued growth. However, it’s important to understand that infill does not naturally lead to affordability, as it encounters substantially increased land and construction costs compared to sprawl.

Real Housing Solutions

We should not pin our housing affordability hopes on waiting for speculative bubbles to burst, or expect that what works in Austin will easily translate to more built-up, geographically constrained cities. The example of Austin at most suggests that a burst of new development in a still-expanding urban area can temporarily moderate average rent prices. However, the market will quickly adjust, and unfettered development can cause damaging local displacement, while leaving a majority of renters cost-burdened.

The most direct and lasting path to housing affordability is to intervene in the market to both preserve and produce affordable homes. Affordable infill is best achieved by public ownership and investment, like that seen in global cities with robust social housing, such as Vienna and Singapore. Here in the US, cities like Seattle are piloting social housing programs that aim to build high quality, deeply affordable housing for a range of income levels. Inevitably, these programs and the funding required to implement them will receive pushback from the wealthy and real estate interests. Only an organized movement of workers demanding real affordability will overcome this resistance. Despite the promises of market urbanists, there are no shortcuts to genuine housing affordability.

Thanks for writing this. I live in a city where people are trotting out the Austin model to justify cutting rental and tenant protections. It is wild how warmed over these arguments are.

the article relies on several economic fallacies, temporal mismatches (using 30-year data to refute 3-year policy changes), and a misunderstanding of how market cycles function.

here is a fact check and analytical breakdown of the key claims.

1. real vs. nominal rents

claim: the "rent collapse" is a misleading snapshot; rents are still massively up over 5 years. analysis: false/misleading due to inflation ignorance. the author looks at nominal rent prices. the comment by "reed schwartz" at the bottom of the post actually identifies the flaw: cumulative inflation since 2016 is roughly 30%.

if rents are flat or slightly up in nominal terms over 5 years, they have likely fallen in real terms (purchasing power).

austin is one of the only major cities where rent growth is currently trailing inflation significantly. ignoring the macro inflationary environment of 2021-2023 distorts the data to make the housing market look more expensive than it is relative to wages and other goods.

2. the "market failure" of the construction pullback

claim: developers stopping construction because rents dropped is a failure of the market model. analysis: this is a fundamental misunderstanding of feedback loops.

the author treats the business cycle as a "failure." when supply exceeds demand, prices drop (good for renters). this price signal tells capital to stop building (allocative efficiency).

if developers continued building despite falling rents, it would represent a waste of resources (capital destruction).

critically, the stock of housing remains. the buildings built during the boom do not disappear when the developers stop building. that permanent increase in supply is what lowers long-term price equilibrium.

3. sprawl vs. infill data mismatch

claim: austin is just sprawling; "half of recent new construction... is single family homes." analysis: misleading/outdated data context.

the author cites a william & mary study covering 1990 to 2020. this is irrelevant to evaluating the "yimby" reforms and supply boom that occurred roughly 2021–2024.

during the actual "austin miracle" period (2022-2024), multifamily permits skyrocketed. in 2023, the austin metro permitted more units per capita than almost anywhere in the us, and the majority of that pipeline was multifamily apartments, not sfh sprawl.

the author is using a 30-year trend of sprawl (which yimbys also oppose) to attack a recent 3-year trend of densification.

4. the geography/land price fallacy

claim: austin is cheap because it has land (sprawl), whereas san francisco is expensive because of geography/maturity. cites land cost of $5.8m/acre (austin) vs $22m/acre (sf). analysis: circular reasoning.

land values are residual. sf land is expensive because you are legally restricted from building enough floor space to satisfy demand. the scarcity is regulatory, not just geographic.

if sf upzoned the "sleepy sunset neighborhood" to allow 50-story towers, the per-unit land cost would drop drastically, even if the per-acre land value spiked.

comparing rural kansas to austin is a straw man; austin is a high-demand tech hub. the fact that it remained cheaper than sf despite similar demand shocks implies that supply elasticity (policy) mattered, not just "available dirt."

5. displacement and "natural" affordability

claim: new development destroys "naturally occurring affordable housing" (noah). analysis: ignores the counterfactual (filtering).

if you don't build new "luxury" units, high-income earners don't leave the city; they buy the older "naturally affordable" buildings and renovate them.

blocking the redevelopment of the northwest austin complex mentioned doesn't guarantee those tenants stay forever; it usually guarantees the building gets bought by a private equity firm, cosmetically renovated, and rented for higher rates anyway—but without adding net new supply to absorb the demand.

6. the social housing alternative & in-kind inefficiency

claim: the only real solution is public ownership (vienna/singapore model) rather than market mechanisms. analysis: this advocates for inefficient in-kind benefits and ignores the root cause of the shortage.

in-kind vs. cash: social housing is an in-kind benefit—a restricted subsidy tied to a specific physical unit rather than the person. welfare economics shows this creates deadweight loss compared to cash. a recipient often derives less utility from a lottery-assigned apartment than they would from the equivalent cash value, which they could allocate to housing or other needs that maximize their own welfare.

paternalism: insisting on building government-owned units rather than redistributing wealth (via ubi or vouchers) is paternalistic. it implies low-income people cannot be trusted to manage their own resources and must have their consumption curated by the state ("treating the poor like children").

removing deadweight loss: the goal is not to "increase supply" as an active state project, but to remove the regulatory deadweight loss (zoning restrictions) that artificially limits the market. once these artificial costs are removed, the market will naturally reach an efficient equilibrium where quantity meets demand. coupling this deregulation with cash transfers (to handle redistribution) solves the problem without the inefficiency of state-planned construction.

summary

the article is a standard left-nimby critique that frames the recent price correction (a success of supply-side economics) as a failure because it isn't a permanent, infinite crash. it relies on data from the sprawl era (pre-2020) to critique the density era (post-2020) and fails to adjust for the massive inflationary wave that makes austin's rent stabilization historically significant.