We Should Weigh the Welfare Impacts of Luxury Housing by Income Level

Harms to Low Income Renters May Outweigh Benefits

(Photo: Stories from rapidly gentrifying Philadelphia, whyy.org)

New market rate housing is supposed to benefit all renters through increasing supply and tempering rent growth. But is it possible that if we look at the different impacts on renter households by income level, and apply income-weighted welfare assumptions, the net impact is actually negative?

Amenity vs Supply Effect

Market rate development, in theory, has the potential to raise rents in the area surrounding the new building, through increasing the desirability and amenities of the neighborhood. The development could attract investment in restaurants, retail, and other neighborhood services catering to higher income residents – leading to a further influx of wealthy households. This “amenity” effect is balanced by the supply effect, whereby new housing competes with existing units to bring prices down.

There goes the neighborhood? (New luxury apartments part of $1B Mpls. building boom”, MPR News/Brandt Williams)

Submarket Impacts

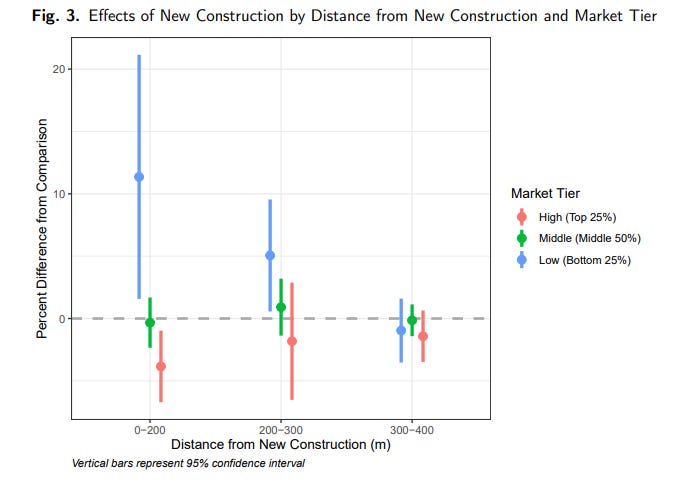

With both effects having an influence, some studies have found a varying impact by submarket, with lower-rent nearby buildings primarily impacted by the amenity effect, and higher-rent buildings primarily by the supply effect. Notably, a study looking at Minneapolis (Damiano and Frenier, 2020) found that low-rent buildings saw a rent increase of around 6% with new market rate construction nearby, while higher-rent buildings saw a decrease of 1.5%. The likely explanation for this is that new luxury units are an effective substitute for existing higher-rent units, but not for lower-rent units. Therefore, this study suggested that the dominant effect on low-rent buildings is that new amenities result in rent increases, which new higher-end supply does little to offset.

“Build Baby Build?” (Damiano and Frenier, 2020)

There are studies often cited by market urbanists purporting to show that market rate construction lowers neighborhood rents (Mast, Reed and Asquith 2023). However, it’s important to note that there has been only limited research at the submarket level, the key finding from Damiano and Frenier. A study in NYC (Li, 2020), found local rent decreases from new luxury construction. When broken down by submarket, there was a stronger rent decline in higher end units, a more moderate decline in mid-range units, and no significant effect on low-end units. It is possible that, if broken down into even more fine-grained submarkets (for example, “quintiles” or fifths, rather than thirds), the lowest end could actually see a rent increase similar to the result of the Minneapolis study. I would be interested to see more research specifically on this question.

Welfare Implications

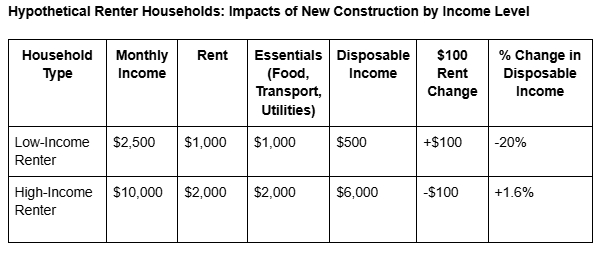

Although the submarket rent increase finding is not yet fully confirmed, it is worthwhile to explore the implications of it being true. While treated as something of a curiosity in housing economics research, I would argue the finding from the Minneapolis study should actually be central to policy decisions around development if confirmed. The reason is that the welfare impacts of even modest changes in rent for low-income households tend to be much more significant than any impact on wealthier households, in relation to household income and especially disposable income.

Consider a hypothetical renter household with a monthly income of $2500 and a rent of $1000. In addition to rent, their essential monthly expenses (groceries, transportation, utilities, debt payments) represent another $1000. Their net disposable income is $500. A $100 monthly rent increase means a 20% reduction in disposable income.

Contrast this with a higher income household. If their monthly income is $10,000, their monthly rent is $2000, and their essential spending is an additional $2000, their disposable income remaining is $6,000. This means that a $100 rent decrease represents only a 1.6% increase in disposable income - nice, but hardly life changing at that income level. The harm to the hypothetical low income household is over 12 times the benefit to the high income household!

Planning for Equity

These figures are illustrative, but indicate the potential of even modest rent increases through the amenity effect to swamp the welfare implications of building new market rate housing in a low income neighborhood. This should have important implications for urban planning and housing policy. New market rate developments in gentrifying neighborhoods may have a disproportionately negative impact on net. Conversely, luxury development in higher income, wealthy enclaves is less harmful, although not without some risks to any low income renters in the neighborhood.

SF Marina Safeway proposal: could be worse places to build this?

While we don’t have enough research to fully confirm the neighborhood-level impacts of new market rate construction by submarket, an understanding of the drastically uneven effects on welfare that apply to different income groups should help inform housing policy. A policy framework that protects vulnerable neighborhoods from displacement, steers construction towards genuinely wealthy enclaves, and ensures a high share of affordable units, could maximize the welfare benefits through a distributional lens.

“There are studies often cited by market urbanists purporting to show that market rate construction lowers neighborhood rents (Mast, Reed and Asquith 2023).”

I have a draft for a housing org i work with (LIMBYHawaii) that talks about moving chains and will be out soon. The papers that Mast et al wrote do not show what their boosters say—namely filtering. The claim rests on an ecological fallacy, ascribing to the individual a population statistic without taking into account selection bias.

For instance in Mastʻs first paper in chicago he tracks the median income in each census tract a mover comes from. The blogosphere has concluded that because the mover came from a low income area, the chain must have reached a low income person.

But even in the poorest census tract in chicago, some 16% of peeps make over 100k, or around 140% of chicago wide AMI.

It is inaccurate to assume people who move from a poorer area to a richer area are themselves poorer when the mere fact of their moving makes it more likely they are better off than their peers!

The whole thing is moot even under the most YIMBY assumptions, but the papers on moving chains released to date just do not show what people think they do.

I'd like to see a broader study of this sort but in a city with some form of rent control (which Minneapolis does not have). The NYC study is closer to this (though most of the city isn't rent-stabilized), and showing no effect on low-end units makes it seem like a pretty explicit net positive to me. (Many rent prices are lowered; larger tax base and voting power for the city; more jobs and customers for local shops/restaurants/etc).

It's hard to imagine, for example, the Marina Safeway increasing rental prices for the most part given nearly all housing in the Marina is rent-controlled.